The Sudan English Teachers Scheme

In the 1970’s and 1980’s there existed a scheme for English teachers to go out to The Sudan to teach in Higher Secondary Schools. Although thousands of young, well educated British and Irish people took part in the scheme, some of them for years, there seems to be very little information about it on the web; which is surprising considering a lot was written about the scheme when it was running, with the ‘Education Guardian’ publishing at least one article a year. There is now a facebook group but so far it only has a few members.

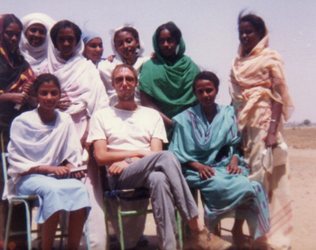

For most, going to The Sudan was a life changing experience, a chance to live and work in a totally different society under radically different conditions. I did two ‘contracts’ the first in 1982 – 83, when I went alone and a second time in 1986 – 87 when I went with my partner Louise; both times I was in El Damazine in Blue Nile province. This article is my account of my experiences, it’s by no means definitive particularly regarding the organization of the scheme or the dates it was operating. If anyone knows more, please get in touch and share your experiences, either on this blog or the facebook group. I for one would like to know more about how the scheme was set up and when it closed down. For me, my times in The Sudan were some of the best of my life and I still have a great affection for the land and the generous and hospitable people who live there.

Recruitment

Every Spring in the 1980’s an ad would appear in the Education jobs pages of the ‘Guardian’ newspaper – ‘English teachers needed for The Sudan’. The qualifications needed were quite straightforward, a degree in any subject and some evidence that you’d travelled a bit preferably off the beaten track. You were then invited to the Sudanese Embassy in Kensington for an interview with an official from the Education ministry and a British former teacher, which was fairly easy going. It was obvious that being able to cope with the living conditions was almost as important as your ability to teach. Successful applicants were then sent for a three day preparation course at the ‘Centre for International Briefing’ which was housed in Farnham Castle in Surrey.

The ‘Centre for International Briefing’ was more used to preparing international bankers or diplomats who were being sent out on foreign postings, so it was a very pleasant place to spend a couple of days. A group of teachers just back from The Sudan formed part of the instruction team; they all looked tanned and lean. They were there to address the tricky issues the Centre’s staff couldn’t, like how do you cope in a world without toilet paper and what is it like to try to teach a class of 70 pupils. We were given talks on living in a Muslim society and medical issues. One ‘expert’ told us that we should get our servants to boil all our drinking water, which bought snorts of derision from the returned teachers. We also had an afternoon class in TEFL, the only instruction on how to do our jobs we received. I managed to wangle another trip to Farnham in ’86, me as a returned teacher and my girlfriend as the newbie. I never worked out who paid for our pleasant days at the castle, the story I heard was that the father of a teacher who had died of malaria somewhere in the south harangued the Foreign Office for letting young people go to such a hostile place so unprepared, and so the British Council stumped up the cash for our ‘briefing’. The only other aid we were given was a copy of ‘Thompson and Martinet,’ an English Grammar; everything else we had to find and pay for ourselves. Luckily, the centre sold essentials like mosquito nets as they were almost impossible to buy anywhere else.

Arrival

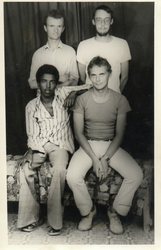

Groups of teachers were sent out during June and July. The flight was included as part of the ‘package’ and everyone went out on the state owned carrier ‘Sudan Airways’. This was always an adventure as the planes seldom left on time which meant that we often got put up in a nice hotel. On my second flight out the auto pilot did not work, so the pilots manually flew the plane the whole way. Flying over Khartoum at night, you looked down on dark city lit only by fluresant strip lights. Piling our kit into a mini bus for the trip to the hotel I was struck by the smell, a heavy, dank, river smell. ‘What’s that smell?’ I asked a girl who looked like an old hand, ‘Khartoum’ she replied. We were put up in a hotel (the Gassa – which has since burnt down) in the centre of the city, a clean place where the helpful staff were used to groups of teachers passing through. We then spent a couple of weeks getting our paperwork sorted out. We were now employees of the Sudanese Government and everything the Sudanese Government did involved a lot of form filling, waiting for papers to be approved and signed, copied onto carbon paper and then filed in great moulding piles that filled the corners of the sprawling Ministry of Education down on the banks of the Blue Nile. There was a full time British liaison officer, an ex teacher, who helped us with the forms and explained how the system worked. As offices only worked in the morning, we had the afternoons to explore the city and get to know our fellow teachers. So we went out to Omdurman to see the whirling dervishes, looked around the old colonial buildings, and had tea at the Grand Hotel. I was fascinated by the city, but I did hear stories of teachers who arrived, took one look around and then demanded to go home, only to be told they had a year’s contract to fulfil. Teachers were allocated to schools around the country with little say as to where you went. On my first tour I was sent to El Damazine in Blue Nile Province with two other guys, Rory McClane, a Scotsman on his second tour, the previous year he’d been posted to Dongala in the north, and Dave O’Neil, a newbie like me.

Finally we were given some money and a pile of signed stamped paperwork; we then had to find our own way to our schools.

Getting started

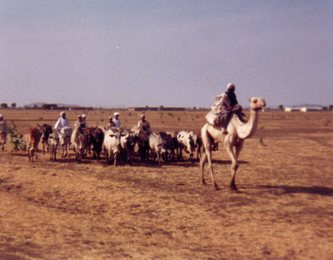

Sudan only had a limited road system, most of it built in the seventies as foreign aid. There was also an antiquated rail network that had been built by the British that was crumbling due to lack of maintenance. The first part of our journey to Wad Madani (the second city) was fairly easy as this was on the road, from there we had to get the train. As the summer is The Sudan’s wet season the countryside was a sea of mud which meant that Ed Damazine was cut off from the outside world except for the train which ran once a week. The engine was a ancient steam relic and carriages wooden boxes with wooden seats. It was heavily overcrowded with as many people on the roof as inside, luckily we managed to get seats but on one journey I had to stand for 12 hours. The train chugged along at a walking pace, stopping at difficult sections and for ‘comfort’ breaks; it usually took a day to go the 100 miles. Getting off the train, I’ve never forgotten the sight of the vivid, emerald green of the grass, dotted with white egrets, back dropped by a grey lowering wet season sky.

As civil servants we were allowed to stay in the Government rest house until we found somewhere else to live. Luckily we befriended a local businessman – Bushra, who had a house to rent. I lived there with Rory and Dave on my first tour, and on my second tour with Louise, my partner.

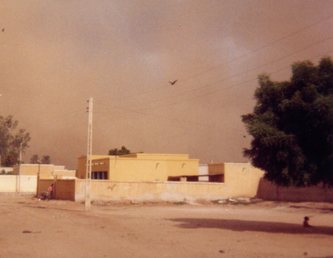

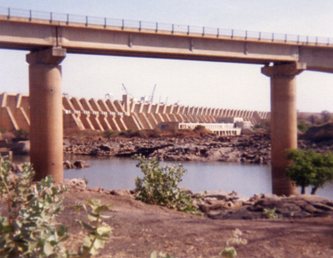

Ed Damazine was a ‘new’ town built in the 1960’s as part of the infrastructure that grew up around the building of the Rosaries dam, which dammed the Blue Nile a couple of kilometres out of town. There was another much older settlement, Rosaries, about half an hour away on the far bank of the Nile which was a more picturesque place to live as the houses (mainly huts) were scattered among a forested area. The sanitation and water supply was not as reliable here and we would have had to commute to work on the school bus, so we decided to stay in Damazine, where the school was within walking distance.

The Schools

We had a few weeks before the start of term to meet the teachers, look around the school and do more paperwork. Nearly all the other local teachers were young men, most of whom had come up through the school system themselves. They were all putting in the years working in a Sudanese school until they could qualify to head off to teach in Saudi Arabia, where they could earn some real money, and so be able to get married.

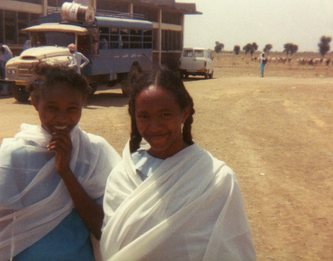

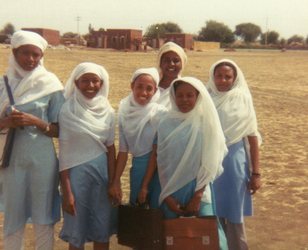

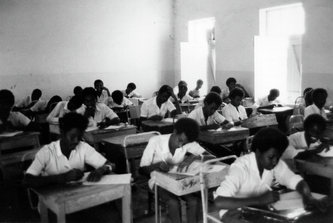

In my first tour I worked at the Girls Higher Secondary School and then at the Boys’ school on my second. Most of the pupils (aged from 13 – 18) were the children of Sudan’s small middle class, children of that age were usually working, so if they were at school and often having to pay for board as well – the parents had to have a reasonable income. Class sizes of sixty or seventy were normal and generally we were only talking to the front two rows, as you went further back, comprehension drifted away.

School hours were from 0730 – 1300, with a break mid morning for ‘breakfast’ usually addas (lentils), which was eaten communally.

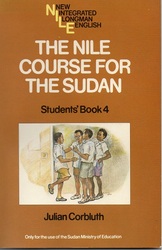

The pupils were all working towards a final exam which was made up of multiple choice questions and if they passed it, it meant that they could then be considered for University. The academic publisher, Longmans, had created a complete range of text books specifically for The Sudan, called the NILE course, which was pretty well put together. The curriculum was fairly rigid, laid down by the Ministry of Education and some of the set texts had obviously been big hits when the men at the ministry had been at school, so we worked our way through plays like ‘Arms and Man’ by Bernard Shaw, which had little relevance to modern Sudan. Of course as the aim of the system was to get the pupils through the final exam, there was a lot of ‘teaching to the test’ with the pupils becoming quite agitated if something wasn’t ‘in the book’. I heard about some English teachers being complained about because many of them had been on TEFL courses and they tried to use modern learning techniques in the classroom. The pupils used to go to the Head of English and say that lessons were being wasted, learning things that weren’t ‘in the test’.

As well as the set books we also used easy readers, shortened versions of novels for language learners, many of which were supplied by the British Council who sent out book boxes to the schools. Again many of the titles were fairly old fashioned. I remember starting ‘Moby Dick’ and trying to explain the idea of whales and sailing ships to girls who had never even seen the sea.

At the end of every term there were exams which the students took very seriously and among the star pupils it was very competitive. We had to make up the questions ourselves, nearly all were multiple choice, then type them onto stencils on an ancient typewriter. The papers were then run off on a bander machine. The big job was marking them all, with the kids endlessly pestering you to know their results.

Discipline was never a problem; most of the students knew that they were fairly privileged to be at school at all. When a teacher walked into a room, everyone stood up and stayed standing until told otherwise. Corporal punishment was regarded as normal. Every school had a solider; a retired NCO whose job was to ring the bell and whip the kids – with a whip. At the girls school the solider was a kindly old gentleman much loved by the students; on the odd occasion he had to do his job, and one day the headmaster had a whole class whipped for being late for a lesson, he reluctantly did it but only used the top 10cm of his whip, and only on the hand. The solider at the boys’ school was a complete contrast, tough as nails; he also ran the schools cadet force. His idea of fun was to chase the boys out of the boarding house, thwacking anyone not moving fast enough.

Of course stroppy adolescents are the same the world over, and they were keen on ‘strikes’ and protests. After the Boys school was disqualified from Blue Nile province school football championships (after fielding a player from another school), the boys organised a protest march, and for the final, the towns police force turned out in riot gear.

Living

Living in Sudan took some getting used to. Firstly there was the weather, arriving in the wet season meant that rain, dampness and mud were pretty constant. In the town off the tarmac roads, everything was a sea of mud, and almost nothing could move outside it. Once the wet finished it did mean that basic commodities could finally get through and even luxuries! We were always absurdly excited when the first Pepsi truck arrived. As the year went on the land became as hard as concrete and great splits appeared in it. Then the weather was bright and cool in the mornings and overall very pleasant.

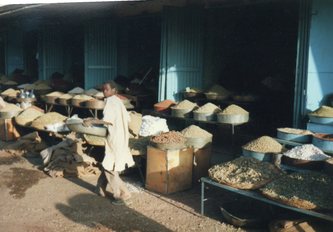

We were lucky to have a large house in a quiet area and surrounded by a high wall, the norm in Sudan, so we had our privacy. Our kitchen was a tap around a drain at one end of the garden and a charcoal burner. The choice of food was fairly limited; we used to make ‘Damazine stew’, basically a stew of onions, garlic, tomatoes and potatoes. When we got tired of this we bought in fuul, the staple dish of the country, brown beans which were boiled for hours, then mashed up with a Pepsi bottle and salad, cumin, oil and occasionally egg added. Like many staple dishes around the world, you can eat it every day and it never seemed to get boring. I still enjoy it even now, buying the beans precooked. When the roads opened we had a good choice of fruit, and fish always served deep fried, came from the Nile. The meat market in the souk, where cows were hacked to bits with axes in medieval conditions, pretty much made us vegetarians.

On my first tour, booze was still legal although Blue Nile was a ‘dry’ province. None was ever for sale and we only ever had it when we visited our ex pat neighbours, American aid workers or engineers at the dam. By ’86, booze was illegal everywhere so the only drink was Aragi, a liquor distilled from dates and usually tasting pretty disgusting. In the big cities, it was very easy to get but in Damazine we got it from the Greeks, an elderly father and son, who were part of the large African Greek Diaspora (Khartoum had a Greek school) and just about hanging on.

Our house had a long drop toilet, a cubicle with a hole in a slab of concrete into which everything dropped into a septic tank, in which huge cockroaches lived and mosquitoes bred. Of course there was no toilet paper so we used the method used throughout the Arab world of cleaning up with water and your hand. Our toilet had an upmarket tap and hose to help you do this, but most just had a plastic bottle.

We had a pleasant veranda area, which we furnished with angrebs, (beds made of wood and strung with rough cord), a table and a few chairs. We had an immersion heater to boil water and or course a short wave radio to listen to the World Service. The bedrooms were the only rooms with ceiling fans, and I have fond memories of being wafted by warm air while lying under the mosquito net. The electricity could go off at any time for an indefinite period and being plunged into darkness meant a scramble for torches and then matches to light candles. At one time the water, which often came out of the tap the colour of Oxtail Soup, went off, and for a few days we had to carry buckets from our neighbours house before we tracked down the man who fixed these things. I’m always amazed when I hear people say they can’t live without their mobile or some other gadget; living without running water for a few days will help you reassess your priorities.

It was fortunate that we’d bought lots of books to read, as we had a lot of spare time to read them. Damazine had a small library in the cultural centre which had been left behind by workers on the dam in the ‘60’s. This was like walking into a literately time warp, lots of authors like Morris West, who were big in their day and at least ten copies of ‘Fear of Flying’ by Erica Jong, which I never got around to reading. We read pretty much everything else out of sheer necessity.

Another constant of tropical living was illness, which used to come and go fairly regularly. Very often you just had a fever, it wasn’t malaria, it was just another unknown tropical fever, this along with diarrhoea and stomach problems were the most common complaints. I had malaria a couple of times on my first tour; chloroquine was fast losing its effectiveness as a prophylactic and we all got it at some time or other. I knew teachers who had typhoid, Hepatitis A (fluorescent yellow eyes) and heard of others, who just went around the bend and had to be sent home. We used to ‘cure’ our own bouts of Malaria by following the instructions in ‘Where there is no doctor’, a medical self help book, so I was really surprised when I got home to learn that malaria was regarded as a medical emergency requiring instant hospitalization.

As was the case with all problems, be it illness, lack of housing or pay not arriving, there was very little in the way of back up. Apart from the liaison officer in Khartoum, who had almost no resources, we had to sort out everything ourselves. So no matter how tough and difficult life became you knew you had to cope with it, we knew the cavalry would never arrive. What it did mean was that was that you made strong bonds with your fellow teachers, for who else could we turn to if not each other?

The Sudanese really took the Islamic code of hospitality to strangers seriously. We were always being invited to tea or for breakfast (more like bunch) and the main social meal of the day. Even chance encounters would result in an invite, regardless of where you were. In the Muslim world, teachers had a status up there with other professions, so even buying tomatoes in the market, the stall holder would address you as ‘teacher’, which was quite a contrast to how the profession was being run down at home. The people always seemed content with their lot, with strong family bonds and a general sense of optimism, which made it a pleasant community to live in. Some things they could not understand about us were our lack of interest in religion, and the fact that Louise and I did not have any children. The inevitable question was, ‘How many children do you have?’ When the answer came there were always exclamations of surprise, and towards Louise, looks of pity.

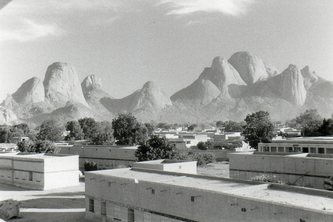

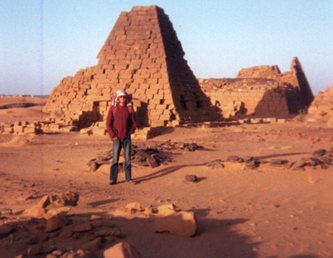

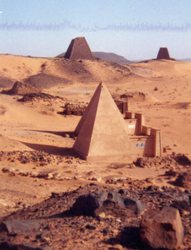

One advantage of being a teacher is that you get lots of holidays and once the road was open you were free to explore the rest of the Sudan. For short breaks we used to visit our ‘neighbours’ up in Sennar and Singa, the towns to the north of us. With people just like you stationed all around the country, you could arrive in any town, ask for the English teachers and expect a warm welcome and a place to sleep and we had lots of people come to stay with us. On one holiday we went up to the bright lights of Khartoum and then along the road to Kassala with its backdrop of domed mountains. On my first tour I carried on up to Port Sudan, visiting the incredible lost city of Suakin and then back across the north of the country to Atbara and the pyramids at Meroe on the Nile. Hard travelling but a great trip.

Leaving

When the final term came to an end we then had to face the long process of leaving the country. In the Sudan this involves collecting paperwork, firstly from your school; you couldn’t get an exit visa without a letter of release from your headmaster. Then packing up the house and heading up to the Ministry of Education in Wad Medani, where you got more papers and your final pay. I spent weeks hanging around here, the second time I did it I read ‘War and Peace’ in a fortnight. Finally up to Khartoum for the last bits of paper, and our air ticket home.

All of it was a real adventure, and we felt we were doing a real job. I met several teachers who signed up year after year, dedicated educators who loved the country and who felt they were making a real difference. Such a contrast to the ‘pay to volunteer’ and do your bit for the third world rackets that are so common today.

Whether we achieved much, it’s difficult to say. Did many of my students, particularly the girls go on to use their English? With the oil industry now a big employer, I would hope that some of them are using what I taught them to secure good jobs in the new economy. Who knows, I’d very much like to go back to find out, or at least see the town and school again.

If you were a teacher in the Sudan, join our Facebook Group