Rwanda

Last year I was travelling in Southern Uganda and being so close to the border it was impossible to resist the chance to visit Rwanda one of Africa’s backwaters; although now it’s a place everyone has heard of but for all the wrong reasons.

Before the First World War Rwanda and Burundi had just been two districts inside German East Africa. When the war started the Belgians had invaded from their colony in the Congo, and having ended up on the winning side, had been given the districts as their part of the spoils. Two tribes lived in the region, the Tutsis and the Hutus, and the Belgians ruled indirectly through the Tutsi chiefs. Although the tribes had coexisted fairly happily up until that point, the Belgians bought in ID cards based on tribe that for the first time allocated everyone to one tribe or the other. As the Tutsis had a privileged place in society including better access to education, this was the beginning of the schism that was to result in disaster in 1994.

Intertribal tensions were already bad before and after independence in 1962, with each tribe periodically rising up to kill the other, which usually resulted in thousands of deaths on both sides. Civil War broke out in 1990, with a Hutu backed rebel army killing thousands of Tutsis and forcing many more into exile. However this was only a precursor to the final solution planned by Hutu extremists whose plan was to rid Rwanda of the Tutsi ‘problem’. This was carefully planned for by the Army and especially trained death squads trained in the forests. In April 1994 the genocide began, and the world looked away, the UN ‘peacekeepers’ fleeing after 10 Belgian soldiers were murdered. The carnage raged for 100 days, after which almost a million Tutus and Hutus (who had refused to take part in the killing) were dead and two million had fled the country.

Nowadays the main reason tourists come to the county is to see Mountain Gorillas in their natural habitat. For others it’s to see the memorials to an event most people thought could not be repeated in modern times. I went in on a day trip organized by the tour leader of the overland truck I was travelling on. Kilagi, the capital was only two hours away from where we were camped in Uganda. The citizens of most Western countries are allowed visa free access to Rwanda, but not Australians, and as half the group was Australian, we had to spend an hour at the border while they filled in the paperwork.

As soon as we crossed the border it was obvious we were in another country, for one thing we were now driving on the right side of the road, changing from the British influenced Africa to that of the French/Belgian. Rwanda is known as the country of a thousand hills and most of journey to Kilagi was along river valleys that meander through the small dumpy hills that cover the country. It seemed a prosperous place too; we passed fields of tea, which as our journey progressed became plantations of Sugar Cane and Bananas. In the small towns we drove through, there were even proper pavements!

Kilagi itself sprawls across several humpy hills with the main roads running in the valleys between them, the houses and buildings climb the slopes; and like the countryside it seemed to be prosperous and well managed place.

Before the First World War Rwanda and Burundi had just been two districts inside German East Africa. When the war started the Belgians had invaded from their colony in the Congo, and having ended up on the winning side, had been given the districts as their part of the spoils. Two tribes lived in the region, the Tutsis and the Hutus, and the Belgians ruled indirectly through the Tutsi chiefs. Although the tribes had coexisted fairly happily up until that point, the Belgians bought in ID cards based on tribe that for the first time allocated everyone to one tribe or the other. As the Tutsis had a privileged place in society including better access to education, this was the beginning of the schism that was to result in disaster in 1994.

Intertribal tensions were already bad before and after independence in 1962, with each tribe periodically rising up to kill the other, which usually resulted in thousands of deaths on both sides. Civil War broke out in 1990, with a Hutu backed rebel army killing thousands of Tutsis and forcing many more into exile. However this was only a precursor to the final solution planned by Hutu extremists whose plan was to rid Rwanda of the Tutsi ‘problem’. This was carefully planned for by the Army and especially trained death squads trained in the forests. In April 1994 the genocide began, and the world looked away, the UN ‘peacekeepers’ fleeing after 10 Belgian soldiers were murdered. The carnage raged for 100 days, after which almost a million Tutus and Hutus (who had refused to take part in the killing) were dead and two million had fled the country.

Nowadays the main reason tourists come to the county is to see Mountain Gorillas in their natural habitat. For others it’s to see the memorials to an event most people thought could not be repeated in modern times. I went in on a day trip organized by the tour leader of the overland truck I was travelling on. Kilagi, the capital was only two hours away from where we were camped in Uganda. The citizens of most Western countries are allowed visa free access to Rwanda, but not Australians, and as half the group was Australian, we had to spend an hour at the border while they filled in the paperwork.

As soon as we crossed the border it was obvious we were in another country, for one thing we were now driving on the right side of the road, changing from the British influenced Africa to that of the French/Belgian. Rwanda is known as the country of a thousand hills and most of journey to Kilagi was along river valleys that meander through the small dumpy hills that cover the country. It seemed a prosperous place too; we passed fields of tea, which as our journey progressed became plantations of Sugar Cane and Bananas. In the small towns we drove through, there were even proper pavements!

Kilagi itself sprawls across several humpy hills with the main roads running in the valleys between them, the houses and buildings climb the slopes; and like the countryside it seemed to be prosperous and well managed place.

|

During the genocide many of the Tutus had been herded into halls and churches where they could be more conveniently killed en mass, and our first stop on the outskirts of the city was a community centre where a massacre had taken place. The community centre was still a community centre and could have been anywhere in world, and looking through the windows we could see a large modern hall, with a stage and lots of plastic stacking chairs. The differences here were the armed soldiers guarding it and in the grounds, large areas of what looked like flat concrete building bases. These ‘bases’ were the sites of mass graves, and beside most of them were concrete memorial walls with the names of the victims etched upon them. We had to interpret what we were looking at ourselves, our drivers knew very little and the guards were not interested in talking to us. Many of the people in my group also had no idea of what had happened in Rwanda, or why we were visiting this site. I gave a short history lesson, and one woman videoed me doing it!

|

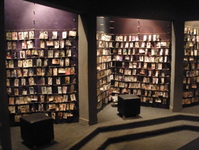

We set off again, around the humpy hills, to a more modern part of town, to a hillside with a view of the centre of the city. Our stop was a large modern building which now houses the Kilagi Memorial Centre which is built on the site of the main mass grave in the city. As the genocide progressed thousands of corpses littered the city or were buried in shallow graves, so the City Council collected them together on one site. Almost a quarter of a million victims now lie there, most of them anonymous, all lying under flat concrete bases.

Security at the Centre is very tight and we had all our belongings searched before we could go in. A fully armed squad of soldiers patrolled around the building and one thing you notice immediately in Kilagi is that there are an awful lot of police and Army about. As all the genocide memorial sites are heavily guarded one gets the impression that not all elements of society have accepted the message of reconciliation and given the chance would inflict further insults on their victims. It reminded me of Synagogues in Germany, which even now are never without an armed policeman standing outside them.

The memorial centre was built by Western donors, and the displays are graphic and informative. They also don’t avoid the fact that the world community and the UN in particular did nothing to prevent what happened. The displays on the genocide convey the real horror of what went on. Some of the stories are simply incomprehensible; like the Catholic priest who murdered his own congregation by herding them into his own church which he then demolished with a bulldozer. With many of the images it’s difficult to work out what you are looking at; until you realize its piles of corpses that have been left to decompose under a tropical sun. It is simply grotesque.

It’s difficult to understand how ordinary people can in one day turn into killers, murdering their neighbours in most brutal ways. Even more astounding, is that the perpetrators having created this charnel house then left the bodies of their victims where they fell – an entire country that was for months infested with the smell and sight of death.

Security at the Centre is very tight and we had all our belongings searched before we could go in. A fully armed squad of soldiers patrolled around the building and one thing you notice immediately in Kilagi is that there are an awful lot of police and Army about. As all the genocide memorial sites are heavily guarded one gets the impression that not all elements of society have accepted the message of reconciliation and given the chance would inflict further insults on their victims. It reminded me of Synagogues in Germany, which even now are never without an armed policeman standing outside them.

The memorial centre was built by Western donors, and the displays are graphic and informative. They also don’t avoid the fact that the world community and the UN in particular did nothing to prevent what happened. The displays on the genocide convey the real horror of what went on. Some of the stories are simply incomprehensible; like the Catholic priest who murdered his own congregation by herding them into his own church which he then demolished with a bulldozer. With many of the images it’s difficult to work out what you are looking at; until you realize its piles of corpses that have been left to decompose under a tropical sun. It is simply grotesque.

It’s difficult to understand how ordinary people can in one day turn into killers, murdering their neighbours in most brutal ways. Even more astounding, is that the perpetrators having created this charnel house then left the bodies of their victims where they fell – an entire country that was for months infested with the smell and sight of death.

|

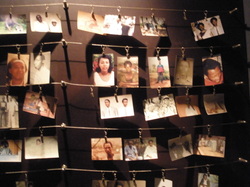

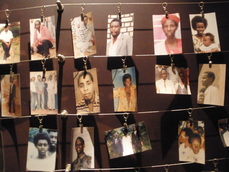

One room in the memorial centre was dedicated to the child victims of the genocide. Visitors were in tears here, it is truly heartbreaking. Images of children are accompanied by a plaque, listing their names, their favourite things, likes and dislikes and a description of how they were killed. Two little sisters – toddlers, stand, surrounded by their toys; they were hacked to death with a machete. A boy of five – shot in the head. Another boy, aged seven – tortured to death.

|

Not surprisingly, everyone in group was quite subdued after what they had seen. We drove into the centre of town to find something to eat and I went for a walk around a business district based on top of one of the hills. It was a Sunday so the streets were deserted and the shops stuttered; only the ever present security guards watched me wander about. Later we went to ‘Hotel des Mille Collines’ better known as Hotel Rwanda, made famous by the film of the same name. During the genocide the African hotel manager allowed Tutsis to take refuge inside the hotel and bribed the death squads to stay away. I’ve not seen this movie but apparently the hotel in the film (which was made in South Africa) is a grand old building, whereas the real thing is a standard tropical luxury hotel complete with pool and manicured gardens.

Having understood what happened in Rwanda, one looked around with different eyes. Imagine the streets of Kilagi littered with decomposing corpses. Look at the people. Anyone in their twenties and younger should be blameless (although some children did take part) but what of those older? Did that man walking down the street hack his neighbours to death? Who knows? What is certain is that a fair proportion of the ordinary people walking the streets do have blood on their hands.

I’ve been to a lot of places where bad things have happened, Auschwitz, Cambodia, Nanjing; but nowhere quite as bad a Rwanda. What makes Rwanda so exceptional is that in comparison with other mass killings, a large part of the population were active participants. In the Holocaust, a relatively small group numbering only a few tens of thousands actually did the killing. In Rwanda, ordinary people were transformed in one day into crazed killers, people who took delight in torturing and humiliating their own neighbours, people who could brutally kill a child.

Where does this evil come from? I saw the memorials and the country but I can’t understand why such an event could take place in modern times, or why it was allowed to.

It’s taken me some time to sit down and write this article, a story I wanted to tell, that I thought would be more measured if I allowed some time to pass. The exhibits in the Kilagi Memorial Centre were designed by a British Charity, the Aegis Trust, which campaigns against crimes against humanity and genocide. For more on these issues and the Rwanda genocide visit their website.

Having understood what happened in Rwanda, one looked around with different eyes. Imagine the streets of Kilagi littered with decomposing corpses. Look at the people. Anyone in their twenties and younger should be blameless (although some children did take part) but what of those older? Did that man walking down the street hack his neighbours to death? Who knows? What is certain is that a fair proportion of the ordinary people walking the streets do have blood on their hands.

I’ve been to a lot of places where bad things have happened, Auschwitz, Cambodia, Nanjing; but nowhere quite as bad a Rwanda. What makes Rwanda so exceptional is that in comparison with other mass killings, a large part of the population were active participants. In the Holocaust, a relatively small group numbering only a few tens of thousands actually did the killing. In Rwanda, ordinary people were transformed in one day into crazed killers, people who took delight in torturing and humiliating their own neighbours, people who could brutally kill a child.

Where does this evil come from? I saw the memorials and the country but I can’t understand why such an event could take place in modern times, or why it was allowed to.

It’s taken me some time to sit down and write this article, a story I wanted to tell, that I thought would be more measured if I allowed some time to pass. The exhibits in the Kilagi Memorial Centre were designed by a British Charity, the Aegis Trust, which campaigns against crimes against humanity and genocide. For more on these issues and the Rwanda genocide visit their website.